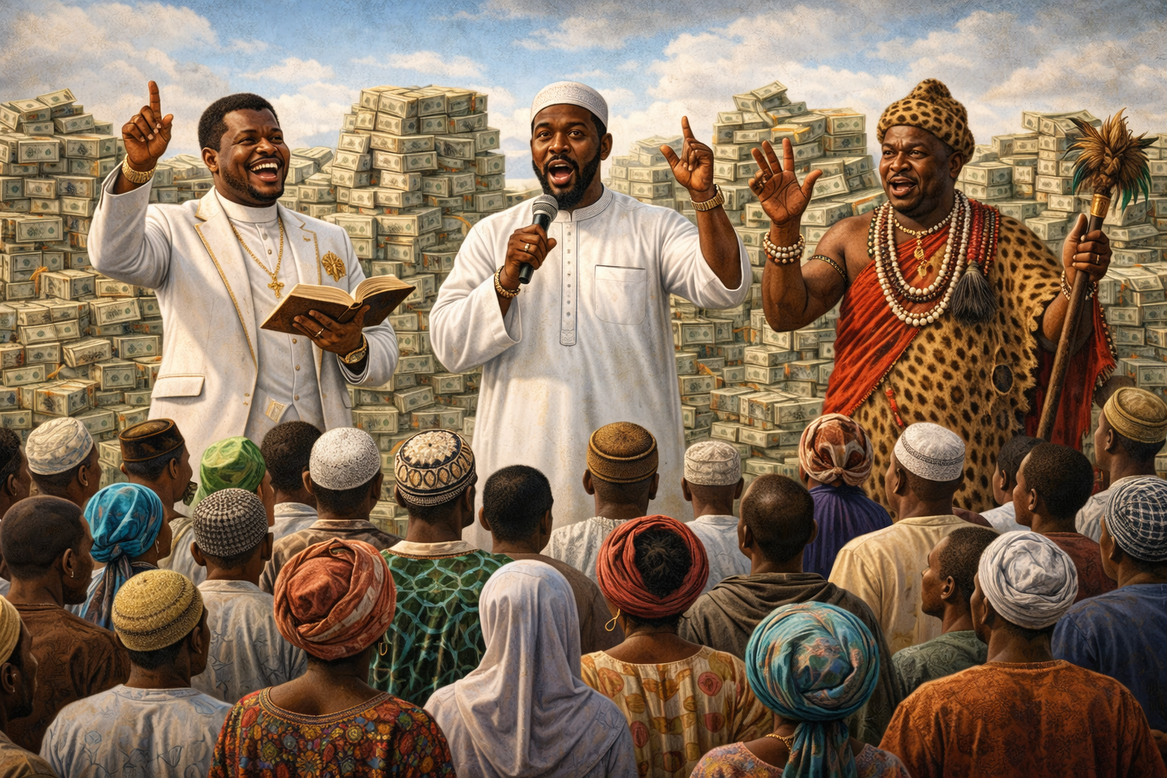

Nigeria is one of the few places on earth where religion isn’t just a belief system but a parallel economic universe. Worship centres have become major players in Nigeria’s informal and formal economies, and increasingly, this is no longer so much about saving souls, but about doing business in God’s name.

Let’s take time to unpack what happens when faith meets capitalism in Naija. Because whether you love God or call yourself secular, it’s impossible to ignore how religion has become one of the country’s most lucrative and least regulated industries.

The Real Size of the Beast

Let’s start with the basic facts that the religious sector in Nigeria is massive. A 2024 Independent report suggests the entire “religious industry” in Nigeria may be worth as much as N500 trillion.

Let that sink in. It dwarfs multiple sectors of the formal economy.

Tithes and offerings aside. We’re talking about educational institutions, banks, publishing houses, broadcasting stations, insurance companies, real estate empires, and even microfinance outfits that are owned by faith groups.

Some mega churches may even command net worths in the hundreds of millions of dollars, own universities, and employ tens of thousands of people.

So what do we call that? Community service? Charity? A business empire with God as its all-covering brand vehicle?

Faith and the Nigerian Psyche

One major driver of this phenomenon is the prosperity gospel, the idea that material wealth equals spiritual blessing. This theology has become the economic engine of many Nigerian churches. Congregants are encouraged to give offerings, “sow seeds,” and participate in spiritual services in exchange for financial breakthroughs.

When pastors link spiritual favour with financial giving, who wouldn’t want a piece of that divine ROI? Whether it’s miracle crusades with special offerings, anointed products, or high-ticket exclusive prayer sessions, every corner of belief becomes part of the transactional economy.

And this isn’t unique to just Christianity.

Withdrawal of the State?

One lame excuse often thrown around is that religion fills the gap left by a weak state. And to be fair, in many communities religious bodies are the most reliable social safety net. Churches and mosques share food, pay school fees, offer emergency cash, help with rent, and basically function as welfare agencies in their own right.

When welfare is mediated through spiritual authority rather than civic rights, what happens to citizens who owe allegiance to no religious faith?

Charity becomes conditional. Help is doled out more like benevolence from a CEO than rights from a government. And in a society where unemployment and poverty are rampant, giving a tenth of your income upward doesn’t necessarily lift you. It may just feed someone else’s real estate fund.

Taxes, Transparency, and the Recent Pushback

For decades, religious organisations in Nigeria operated in a legal grey zone where they didn’t have to pay tax on tithes, offerings, or many of their businesses. Their operations were seen as charitable and thus exempt from income tax.

But the 2026 tax reforms are trying to change that. Under the new tax regime, Nigeria aims to bring religious organisations into a formal fiscal framework.

Income from commercial ventures like schools, hospitals, retail outlets, etc are now taxable. Every donation and transaction claimed as exempt must be digitally traceable.

As regulators put it, the days of “cash in the offering plate, no questions asked” are numbered, and some big religious empires are sweating.

Economists even argue that bringing churches and mosques into the tax net could unlock billions of naira in revenue, money that could be used for infrastructure, jobs, and public services, if government officials don’t pilfer the funds, as usual .

But it’s controversial. Many religious leaders see this as government interference with sacred spaces. Some congregants see it as an attack on faith itself.

Yet, without transparency, huge sums of money remain beyond civic oversight, and that’s a problem for a nation struggling to build roads, hospitals, and schools.

Power, Influence, and Politics

In Nigeria, religion isn’t content with just economics. It wields political power. Faith leaders are kingmakers, influencers, lobbyists, who are often more trusted than politicians. The wealthiest ‘men of God’ rub shoulders with former presidents and governors, sometimes eclipsing political party power with spiritual clout.

Whether it’s mobilising millions of worshippers or shaping policy preferences, religion’s impact on politics is huge and unquantifiable. That power is an extension of financial muscle, and in Nigeria, money often equals authority.

The Ethical Tightrope

It can be argued that religious capitalism commodifies belief. When spiritual services are tiered by price, faith risks becoming a luxury brand. When pastors fly private jets and live in gated estates built on congregants’ tithes and offerings, questions arise about where divine mission ends and personal profit begins.

On the other hand, some say these structures create jobs, deliver services, and even foster economic growth. Nigeria’s religious economy is huge, and many of its institutions drive real commerce.

But we must tell ourselves the truth that religious capitalism thrives most when accountability is weakest. Lack of transparent reporting, tax exemptions, and emotional appeals blur lines that should be distinct. Charity vs commerce, faith vs finance, sacred purpose vs profit motive.

If you’re wondering where Nigeria’s religious capitalism is headed, consider that religion has become so intertwined with everyday life that its economic footprint rivals entire industries. Yet, regulatory oversight, civic transparency, and ethical accountability lag behind.

What’s certain is that in Nigeria, faith is big money, big business, and big influence. And until there’s clarity around how these sectors operate, how they pay tax, and how they serve citizens beyond the pulpit, the debate about whether religion is a business or a blessing will only intensify.

In the end, a healthy religious ecosystem should enrich souls without impoverishing citizens, serve communities without exploiting vulnerabilities, and participate in the economy without escaping accountability. That’s the challenge for Nigeria and the conversation starts with honesty.

Your opinion matters, please leave a comment